A 67-year-old woman with chronic back pain underwent a lumbar epidural steroid injection by Dr. R.

She went home but began to have severe back pain that was worsening.

Her daughter called Dr. R’s office, and they told her to go to the ED if PO medication didn’t adequately treat the pain.

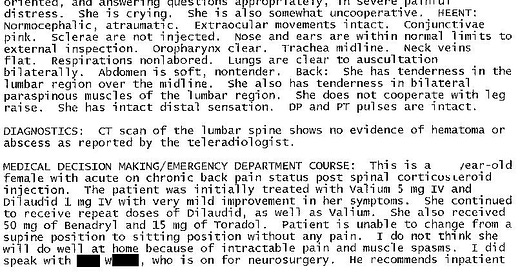

She was seen by Dr. O in the ED.

The patient was noted to have severe back pain radiating down her right leg.

She was unable to raise her right leg off the bed, but it wasn’t clear if this was due to pain or weakness.

Dr. O ordered lorazepam and hydromorphone, and her pain improved from 10/10 to 5/10.

The patient denied saddle anesthesia and loss of bowel or bladder control.

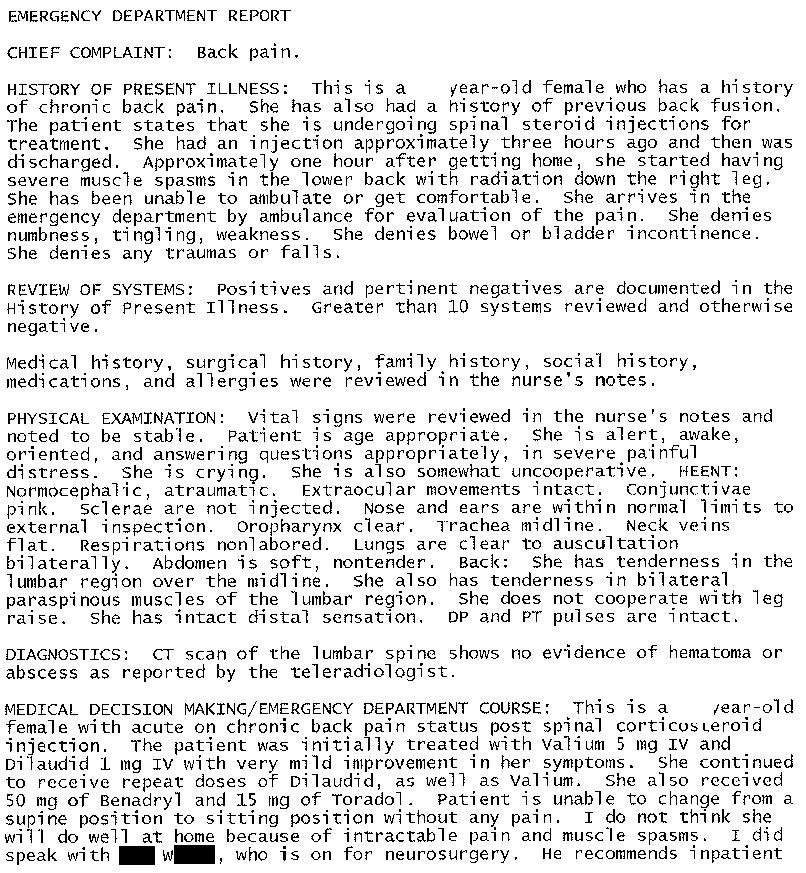

Dr. O ordered a CT of her lumbar spine.

The nighthawk radiologist saw no acute findings, but no written report was ever documented in the chart.

The patient could still not sit up without having extreme pain, much less make an attempt to get up and walk.

Dr. O consulted neurosurgery and the anesthesia/pain service. Neither had an objection to admitting her as long as they didn’t have to do the admission.

The patient was admitted to the hospitalist.

Become a better doctor.

Join thousands of doctors on the email list.

The ED physician’s note is shown here:

The next morning, the hospital’s radiologist reviewed the images and wrote this report:

The patient’s exam worsened, and an MRI confirmed epidural hematoma.

She underwent emergency spine surgery but was left with permanent weakness in her legs, although able to walk with a walker.

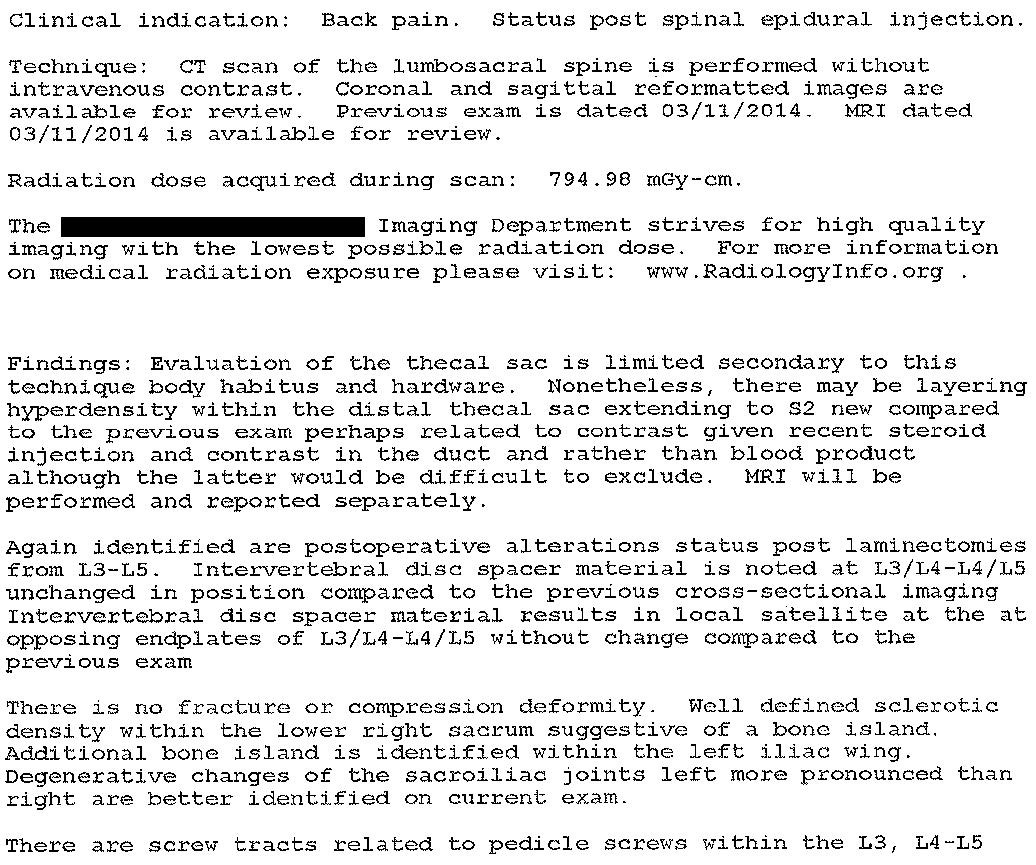

The patient sued the hospital and the ED doctor.

The ED expert witness opinion is shown here:

The ED physician was deposed.

It is very rare to find a copy of an entire deposition (I usually only find 2-3 page excerpts), but it was included in the court records this time.

It is attached below for those who are curious to read what the plaintiff’s attorney asked her and how she explained her care.

A confidential settlement was reached before trial.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

This may anger some readers, but my opinion is that testing reflexes in the ED is useless in 99.999% of patients, including this one. It’s nearly impossible to get patients with severe back pain into a position that allows high quality reflex testing. They are so tense and resistant (even after giving pain medication) that the exam can’t be conducted properly and any results are not reliable. It’s fine if you want to do them, but you should be honest with yourself that the primary reason is for medicolegal defense (so the opposing attorney and expert can’t make you look stupid on the stand by pointing out you didn’t check reflexes), not to actually make a diagnosis.

Another obstacle to checking reflexes in the acute care setting is that medical students and residents are taught how to do a neuro exam on patients who are sitting upright in a chair. This is not how you will encounter patients in the hospital or ED. They will be lying down, screaming in pain, and rolling from side to side. Reflexes should be primarily taught in the supine position. This video is a good refresher on how to do the exam in a supine position. We do learners a massive disservice in how we teach reflexes, and educators (especially for generalists and in the acute care setting) should focus primarily on the supine examination.

One of the big problems in this case was the lack of documentation from the overnight radiologist. Apparently there was no written report nor documentation of the discussion with the ED physician, which I find quite bizarre. This left the ED physician in a vulnerable spot. I’ve never worked in a hospital like this, but if you are receiving verbal communication and there is no accompanying report, you should aggressively document what you were told.

The next day’s final radiology report certainly raised the possibility that epidural blood or hyperdense fluid may be present, but didn’t explicitly identify compression of the thecal sac or nerve roots. This can be a challenging diagnosis because imaging doesn’t always give you a clear diagnosis, it just gives you hints. The bedside clinician needs to be ready to combine the clues from the radiology report with the history (recent procedure that could plausibly cause an epidural hematoma) and examination (leg weakness and severe pain) to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Documenting consults is an important part of risk-mitigation. Higher risk situations demand more lengthy documentation. It’s best to document who you spoke with, what you explicitly told them, what diagnosis you were concerned for, and what they recommended. I’ve seen cases in which specialists try to weasel their way out of liability by claiming they were never told key information (or try to claim that a call to discuss a specific patient’s care wasn’t an actual consult), and having contemporaneous documentation is your best defense against that. In most cases I only document a few words, but in high risk situations I might document a paragraph. The doctor in this case did an ok job, but more aggressive documentation of the discussion with the neurosurgery PA (the expert mistakenly thought the PA was the attending neurosurgeon) could have been helpful.

MRI access often plays a role in spinal cord catastrophe lawsuits. Especially 5-10 years ago, many hospitals willfully limited MRI access and purposefully placed numerous road blocks in place that induced doctors to provide bad care for the sake of the bottom line (staffing MRI techs 24/7 is expensive). MRI was certainly the better imaging modality in this case, but the patient presented at 5pm and the hospital administrators apparently did not want to enable their physicians to treat patients appropriately after regular business hours. Better hospital MRI policies would have given the patient a much better chance of avoiding this outcome.

It seems that the ED doctor was the only physician sued in this case (although it’s possible that other doctors settled before the lawsuit was filed). It is a miscarriage of justice that the ED physician single-handedly shouldered the liability for a complication of another doctor’s procedure, and for inpatient delays in diagnosis despite having the appropriate specialists consulted. She was faced with a challenging diagnosis that was so early in it’s course that it did not exhibit the textbook symptoms, inability to get an MRI despite her hospital having an MRI scanner, and no clear indication to transfer given lack of classic symptoms. I don’t know if the other doctors were necessarily negligent, but it’s certainly not right to blame the ED physician after she was abruptly forced by fate into a situation in which everything was going against her. That’s like putting a new pitcher on the mound in the ninth inning of a baseball game that your team is losing 12-0, and then being mad at them when you lose 13-0. This is just a tiny example of the injustices that slowly mount and result in the average female EM doctor quitting medicine within 10.5 years of residency graduation.

For any newer docs or those who have never gone through a lawsuit / deposition -- I'd HIGHLY recommend a close read through this deposition (forewarning, it's lengthy). Yes, it's tedious, but that's the point. Take a few minutes and read through -- think about sitting there, stressed out, nervous, and how you'd answer each of these questions while a bad-faith actor is leading through you this series of questions. Notice the level of detail they ask about. Every. Thing. in your chart is going to be turned upside down and shaken out. This is all to get you to slip up about something -- anything -- that can then be used against you. Remember, the person(s)/jury judging whether or not you screwed up (and owe millions of dollars) has absolutely no medical training. They're the ones asking why you aren't prescribing antibiotics for their viral cough, and wondering why you won't order a CT for their recurrent migraine headache. The deposition has little to do about actual medical fact, and all about painting you as a bad, sloppy, inconsiderate, short-cutting doctor.

A trained eye will notice how the plaintiff attorney gets this doc to give up a lot of ground without much effort. There's a lot of of questions that are much about nothing, and then they'll strike with something that might seem innocuous but is actually pretty harmful to the defenses' case. Think of how long they spend just on getting the doctor to explain their practice training, schedule, etc was. All just fluff to wear you down when you're most on guard (or even prompt a slip up or two that don't matter for the case, but serve to make you nervous). There's a lot of misdirection here.

One that just jumps right off the page to me is how they get the ED doc to essentially admit they violated standard of care. They got them to admit first, that there IS a standard of care for MRI (that doesn't change!), and then slowly cornered them into the fact that their documentation didn't exclude the near for an MRI. Standard of care is for THEM to argue, not for you to freely give up (even if it's obvious).

The antidote to all of this is to contextualize EVERYTHING, and never speak in absolutes. The jury has NO idea about what it takes to order an MRI after hours -- so explain it to them. Don't paint it like you just click it in the chart and it happens! Clearly that wasn't the case here (or frankly at most hospitals, even now, in 2025). I was shaking my head as the attorney asked what it took to order an MRI and the doc was just describing the buttons they needed to click...

Being an ED doc is freaking hard, and there are landmines everywhere. We know very well the world is all but black and white, and yet, this is how the plaintiff attorney will set up every question --- yes or no XXXX (question framed exactly how they want it to read and imply). Every question in the deposition must be treated as a trap, and your best defense is to contextualize it into how YOU interpret the spirit of the question. Don't use their words, use yours.

Did spine surgery for about 40 years. Agree with your conclusions re somehow ‘pinning’ this on the ED was bullshit. Also, may have missed it, but did not see a rectal exam was done, which imo:experience is more useful : telling than testing reflexes in the supine position. DJS MDJD