A 59-year-old woman presented to the ED with abdominal pain, 8 days after having a sigmoid resection for diverticulitis.

She was diagnosed with a small bowel obstruction and admitted to surgery.

Several days later, she became short of breath.

The surgery resident (Dr. L) ordered a CTA chest to assess for PE.

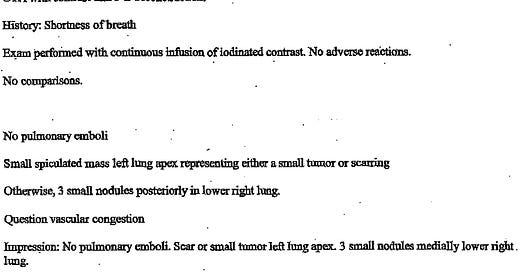

The scan was done on June 18, 2004, and was read by Dr. W (attending radiologist):

During rounds, the surgery resident advised the attending (Dr. C) that there was no PE.

The patient underwent a lysis of adhesions, and a pelvic abscess was drained.

After a long hospital course, she was discharged home.

Over the next few years, she had numerous visits with her PCP (Dr. K).

In June 2012 (8 years after the CT scan), she was seen for abdominal pain and weight loss.

She had a CT abd/pelvis that showed a small liver lesion.

She was referred to GI.

GI ordered an MRCP, which showed a 2.2cm mass in the tail of the pancreas, with 3 metastatic liver lesions.

Further investigation also revealed an 8cm x 6cm left lung mass.

She underwent biopsies of one of the liver lesions and the lung mass.

She established care with Dr. T (oncologist), who treated her for stage IV lung cancer.

After a few months of treatment, she passed away in January 2013.

Join thousands of doctors and attorneys on the email list.

Free and paid options available.

The patient’s family filed a lawsuit against the surgery resident, surgery attending, and the radiologist who were taking care of her when she had the original CT scan in 2004.

They also sued her PCP (Dr. K) for not realizing she had a lung lesion while caring for her for 8 years.

The defense raised numerous objections to the plaintiff’s claims.

A radiologist reviewed the case and opined that the lung cancer arose from a different location than the lesion mentioned on the June 2004 CT scan.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

A pathologist for the defense also reviewed the biopsy slides.

He raised the possibility that the patient actually died of pancreatic cancer, not lung cancer.

The judge dismissed the case against the radiologist due to the 5-year statute of limitations.

Following the radiologist’s dismissal, the surgery resident, surgery attending, and hospital were voluntarily dropped from the lawsuit by the plaintiff.

The reason for dropping them is not listed, but one would assume that the plaintiff realized that the claims against these other parties would also be dismissed.

Dr. K was left as the only remaining defendant.

The case went to trial.

The jury returned a verdict in favor of the defense.

Become a medicolegal expert.

Learn from lawsuits to help you avoid common errors.

A bill for one of the expert witnesses was included in the court records:

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

I’m frankly unsure what to make of the defense’s counterpoints. The original lesion was in the apex of the left lung, and the large mass was discovered there as well, which seems very suspicious. An 8cm x 6cm mass seems big enough that it would distort the anatomy and preclude a conclusive differentiation between the anterior and posterior aspects of the lung apex. The lesion was described as “spiculated” by the radiologist, which is much more suggestive of a neoplasm than an infectious or inflammatory process.

If this patient truly had pancreatic and lung cancer simultaneously, she had incredibly bad luck. I personally haven’t ever seen a patient with lung cancer that metastasized to the pancreas, but apparently various types of lung cancer are known to do so in rare occasions.

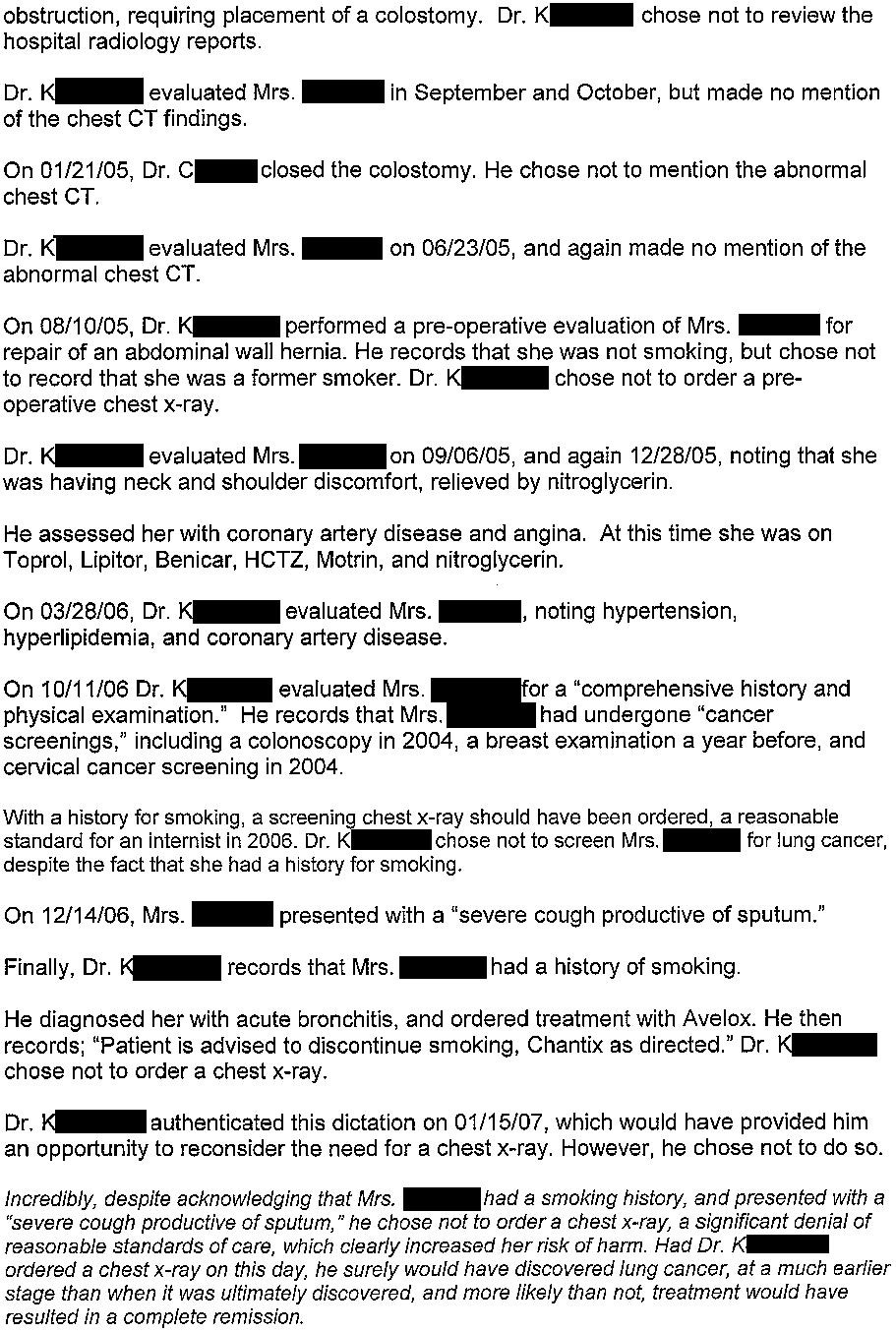

I appreciate details in an expert’s note, but he really took it too far. The relevant issues could have been addressed in less than half the space. He focused on the failure to order a chest x-ray to screen for lung cancer in a smoker. I don’t know what the standard was before the 2013 USPSTF guidelines for annual low-dose CTs in smokers, but there’s a chance our modern screening would have prevented this outcome.

Lawsuits about incidental findings on imaging are unfortunately common. They almost all follow the same pattern: a test was ordered to look for a specific diagnosis, and an unrelated and incidentally-identified lesion was not followed-up by the clinician. PCPs already have too much to do, but reviewing a patient’s recent imaging, even if someone else ordered it, can avert disaster. Pennsylvania has taken an interesting approach to this issue with Act 112, which mandates that diagnostic imaging facilities notify patients directly that a “significant abnormality” exists. I think the overall idea of this law has potential, although the current implementation seems questionable and it would not have prevented this lawsuit because inpatient and ER scans are exempt.

The plaintiff's expert using the word "chose" repeatedly in their report is rather irksome. The expert cannot know why something was done or not done, e.g., ordering a CXR or not documenting smoking history. Unless the treating doctor specifically documented that they considered and chose not to order a CXR, I think that the expert is using overly aggressive language which assumes intent when it may not exist.

Not gonna lie, while plaintiff expert's opinion was a bit overboard on the detail, it seemed pretty damning on paper (at least to my eyes, having no experience with cancer screening guidelines). The issue is when they put all their chips on "this is the cancer you missed 8 years ago," they're vulnerable to the defenses we saw here, i.e. "well actually this looks more like pancreatic cancer" or "it's a different lung cancer." Standard of evidence for med mal is "a preponderance of the evidence," or loosely, "more likely than not." So if the defense could make it a coin flip in the jury's mind, they get the verdict.

Maybe I'm not clear on something though: I thought the statute of limitations starts from the time the patient *learns about* the alleged negligence or its consequences. Maybe that's specific to state law.