A 12-year-old boy developed neck pain over the course of several months.

He was taken to his pediatrician several times, but conservative treatment was unsuccessful.

An MRI was ultimately ordered that revealed a C3 vertebral body lesion.

He was referred to a large academic hospital.

A multidisciplinary team including pediatric neurosurgeon, heme/onc, and orthopedics saw him.

The pediatric heme/onc note A/P is shown here:

The patient underwent MRI/MRA and CT of his neck.

After further consideration, the neurosurgeon (Dr. D) recommended an open biopsy and fusion.

Join thousands of doctors and attorneys on the email list.

Free and paid options are available.

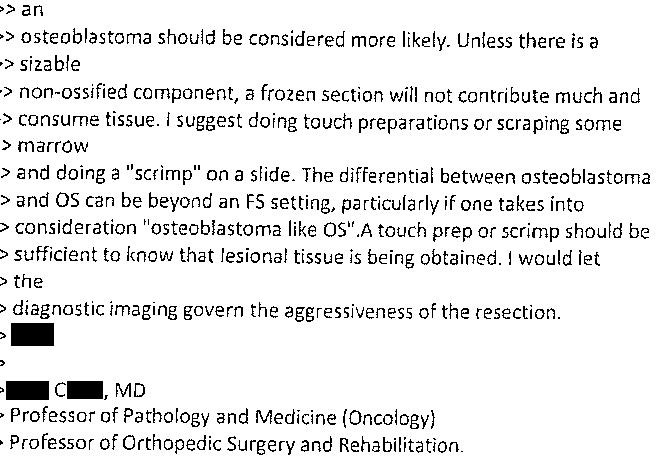

Due to the fact that the diagnosis between osteoblastoma and osteosarcoma was unclear, Dr. D (neurosurgeon) sent an email to Dr. V (one of the head pathologists, board certified in anatomic pathology and neuropathology) to discuss the planned biopsy.

Dr. V responded and copied multiple colleagues.

Dr. C responded.

Dr. D replied that the imaging was not giving a clear diagnosis.

Dr. C suggested that instead of having neuroradiologists review it, that the MSK radiology group should give their opinion.

One of the MSK radiologists reviewed the images and emailed Dr. D.

Dr. D responded to the MSK radiologist and copied multiple pathologists involved in the email chain.

The following day (in the morning before the surgery), a pediatric pathologist wrote this email to the head pathologist (Dr. V) who had been leading communication with Dr. D.

Dr. V notified Dr. D about the pediatric pathologist’s recommendation.

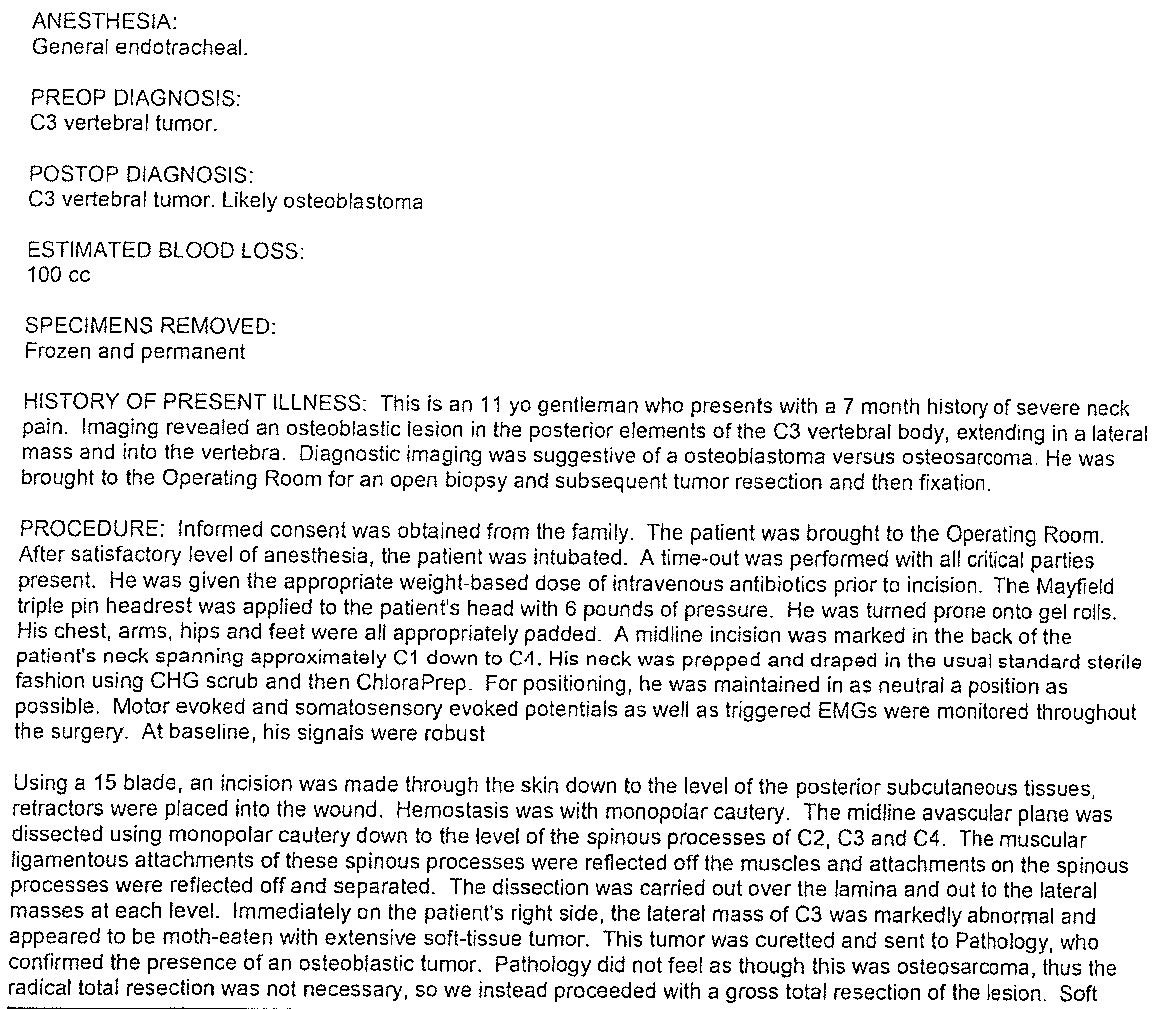

The surgery went ahead later that day.

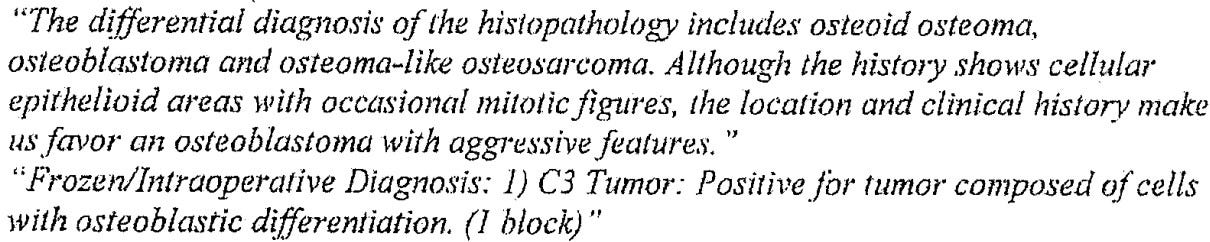

Frozen sections were done during the operation.

The written report from the frozen sections is shown here:

It is not clear if the surgeon spoke with the pathologist on the phone or read the written report.

Regardless, he decided it was osteoblastoma and elected to proceed with limited local resection, C3 laminectomy and C2-C4 fusion.

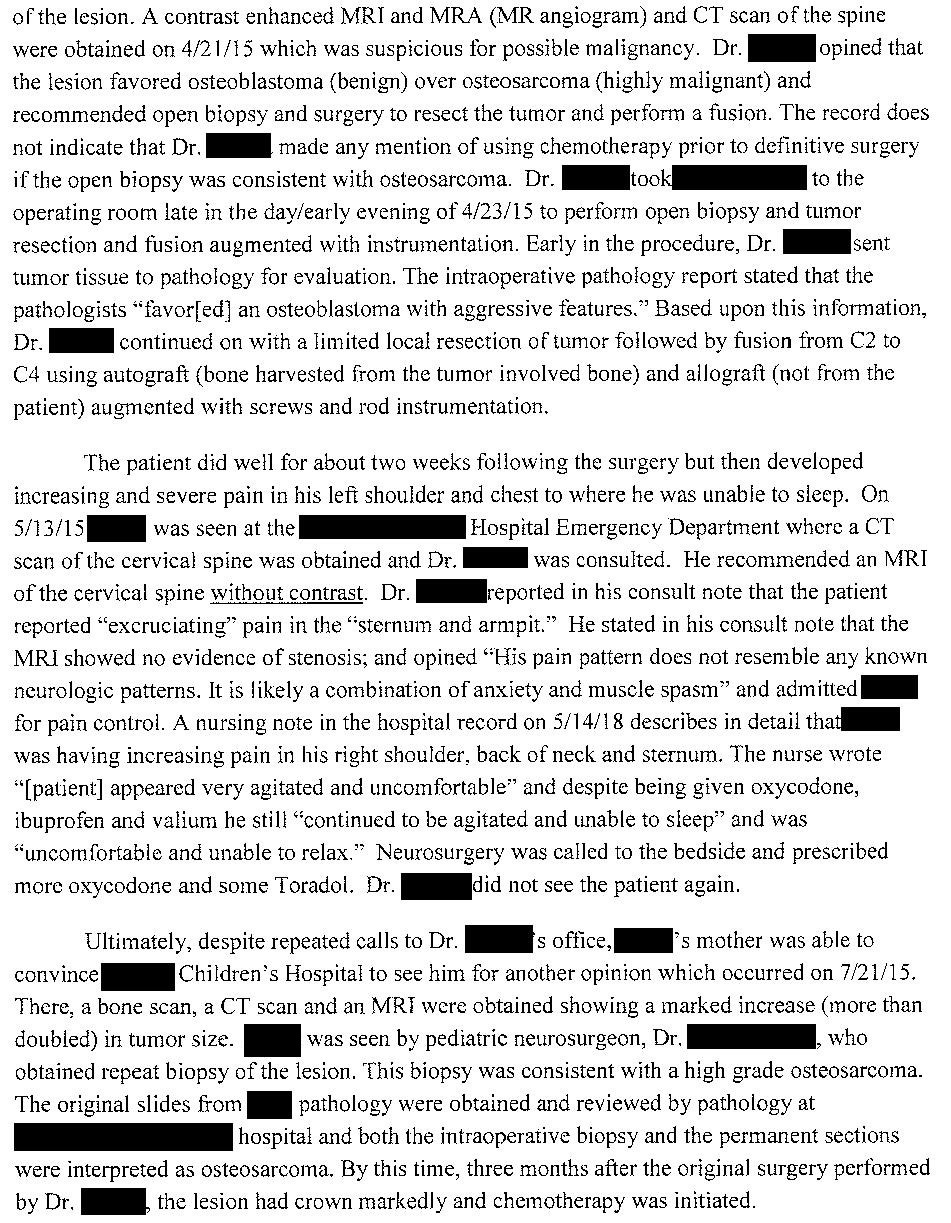

The operative note is shown here:

The results of the permanent sections were not included in the court records.

However, the court records stated that the pathologists “failed to make the correct pathologic diagnosis of osteosarcoma even on permanent sections”.

Unfortunately the child had worsening pain in the weeks and months following the operation.

He was seen at various other well-respected academic institutions, had a repeat biopsy, and was diagnosed with osteosarcoma.

He was treated with multiple subsequent surgeries and chemotherapy.

He tragically passed away several months after the initial operation.

Become a better doctor by reviewing malpractice cases.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

His family filed a lawsuit against the neurosurgeon and multiple pathologists.

They allege that the tumor was misdiagnosed, robbing the patient of the opportunity to have his osteosarcoma treated appropriately.

They note that the autografting done during his original procedure likely seeded osteosarcoma throughout the entire surgical area, causing rapid progression of the cancer.

Part of the allegations against the neurosurgeon include that he misrepresented his expertise:

Notably, the neurosurgeon completed a pediatric neurosurgery fellowship and is the chair of pediatric neurosurgery at an Ivy League institution.

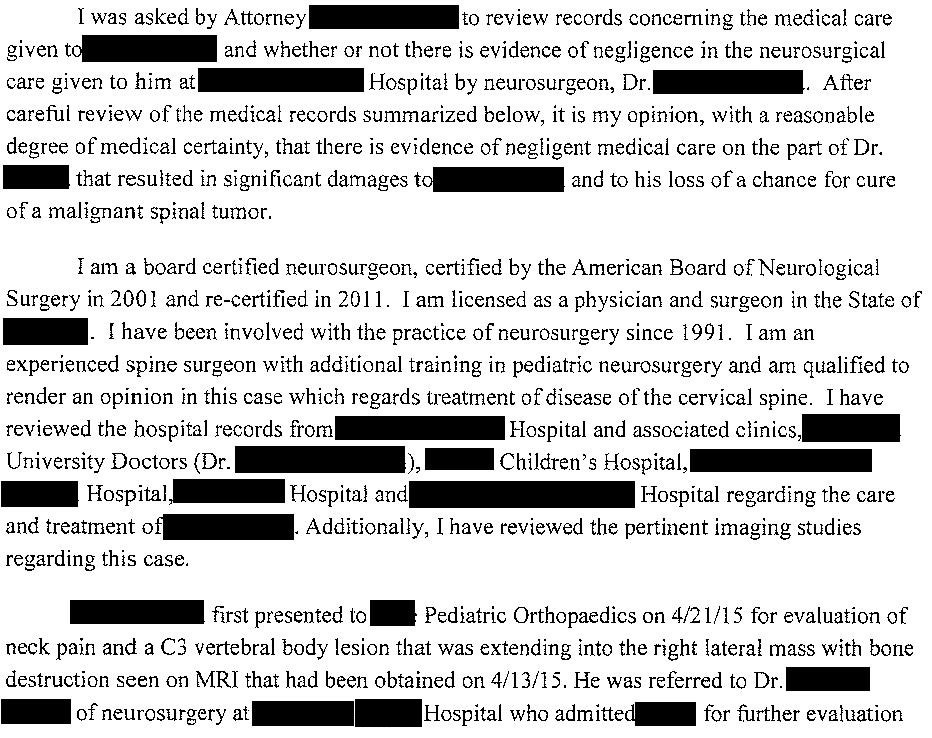

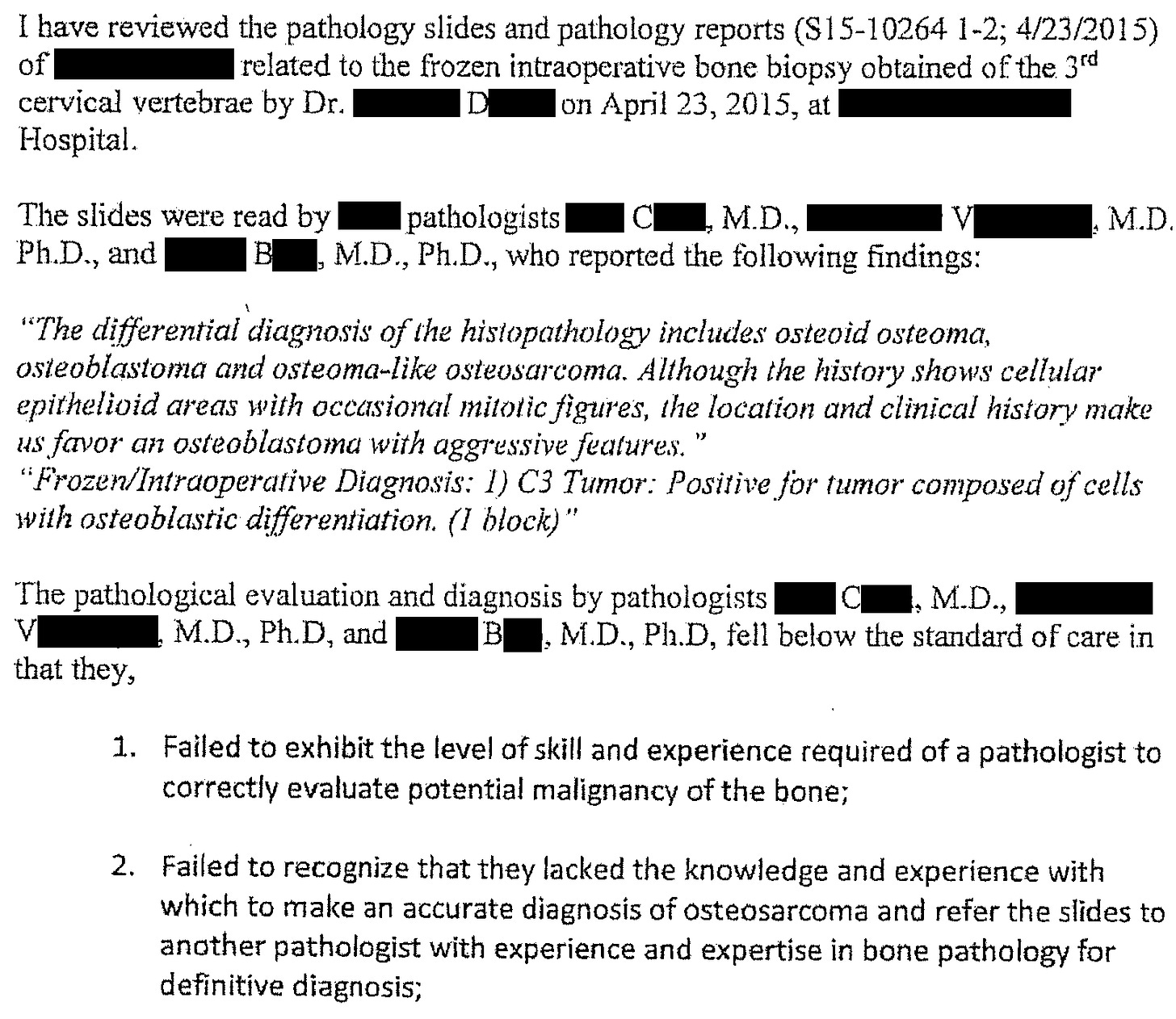

An expert witness wrote the following opinion:

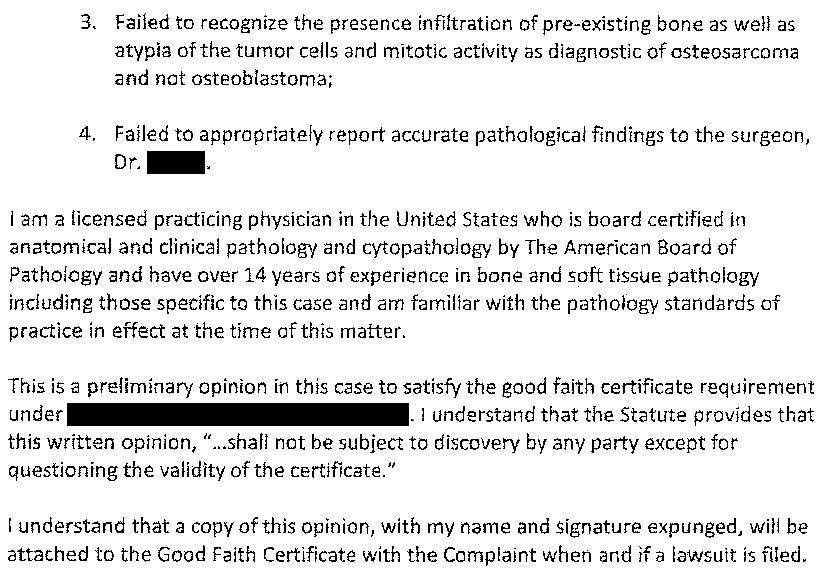

Several pathologists who reviewed the slides were also named as defendants.

A pediatric heme/onc doctor was also hired by the plaintiffs.

The defense hired multiple experts, including a neurosurgeon:

An anatomic pathologist was also hired by the defense.

The defense hired a pediatric heme/onc specialists as well.

The family has offered to settle the case against numerous defendants (the neurosurgeon, multiple pathologists, the hospital where this occurred, and the affiliated medical school).

They are requesting a total of $8 million from all parties.

All parties reached a confidential settlement prior to trial.

CME credit is available for all cases originally published after February 1, 2025 (unfortunately that means this case isn’t eligible).

Purchase a CME-level subscription and start collecting CME credits.

MedMalReviewer Opinion:

This is a very difficult case to defend given the optics associated with a child dying a painful death, coupled with the fact that the neurosurgeon may have accidentally worsened the disease. I am not in a place to lecture subspecialists with some of the most impressive academic credentials in the world, but obviously it is imperative to make sure that the diagnosis is correct before proceeding with resection and that autografted tissue does not contain aggressive neoplastic cells.

The chain of emails is something I’ve never seen before in a med mal case. Almost anything you write can be discoverable (with possible exception of peer review depending on the jurisdiction), so keep this in mind when writing about patients outside the medical record. I’m not sure if these emails would have helped or hurt the defendants if it had gone to trial. It is clear from these emails that all parties were making an effort to be diligent and make a good decision, which the jury may see in a favorable light. However, several of the pathologists expressed hesitation about getting a frozen section, and yet the surgeon and pathologists pressed ahead with a frozen section anyway. It seems that the permanent section was also read as osteoblastoma, so limiting the first surgery to biopsy and returning later for definitive treatment likely would have produced the same outcome in the end.

It is unclear if the family was made aware of the possibility of osteoblastoma vs. osteosarcoma. Having a frank discussion with them about the equivocal nature of the pathology report and documenting their involvement in this extremely risky decision could have helped them understand the challenges and lessened their shock when the bad outcome was discovered.

The vast majority of osteosarcoma cases are in extremity long bones. Axial osteosarcoma is very rare. When it does happen, it is usually found in the lumbar or sacral spine, not the cervical spine. This case report discusses a case of cervical osteosarcoma. Although some aspects of the case are different, it is a great review of this topic for those of us who don’t think about it on a daily basis in our practice.

Previous Cases:

"Retired" general orthopedic surgeon who had his license suspended by KY in 1994. Case #467, so take my opinion in context and with a huge grain of salt. It seems to me this the case boils down to whether the initial surgery should have been an open or percutaneous BX rather than "winging it"on the OR table with a possible one shot definitive procedure.

Because of the lack of certainty inherent in some cases of osteoblastoma vs osteosarcoma, even when special stains are available on a delayed basis as opposed to relying on a "shooting from the hip" determination on the spot by frozen section, even with the most careful review of preoperative radiology studies notwithstanding, my opinion is that this poor kid was a goner, no matter what. Yes, bone auto and allografting made it worse, but expecting to resect the tumor completely and getting a cure is unrealistic when it is in such a vital strategic location with vital structures crowded all around even if a "complete" C3 corpectomy with all apparent margins had been performed compared to a complete resection of an expendable bone like a fibula. A limited Bx would have introduced contamination anyway. It was a total C-3 corpectomy. Would that have been deemed too aggressive in what may have simply been an osteoblastoma?

By soliciting an expert opinion, basically this is in a way analogus to "survivorship bias." Any expert already has been tipped off that there was something wrong if this is the only case he is asked to review. It would be interesting to slip in cases where the outcome was not disclosed, and see how many of these other cases that expert "criticizes"and then determine which of these cases he was correct in his predictive opinion. The fact that case presentations are the staple of medical conferences where attendees constantly disagree on diagnosis and treatment relegates this to Monday morning quarterbacking.

I understand the reference to the word "reasonable" as in reasonable care here in the expert's opinion. But what are the defensible limits of reasonable care? For example, diagnosing this case as osteomyelitis and placing him on vancomycin empirically with no blood cultures or lesion aspiration could be care that fell below a "reasonable standard." But not this. This is just as the late great Neil Peart wrote about so elequently in his song "Roll the Bones. "

"We come into this world and take our chances. Fate is just the weight of circumstances."

This kid was dealt a rotten hand. by fate.

This is a freak case to be honest. Osteosarcoma in cervical spine that did not burst out of the vertebra for months (assuming this because otherwise it would look more malignant in the imaging, ringing alarm bells. I don't know if closing the patient at that point would make any difference. Sad case for both parties.