A 38-year-old firefighter was diagnosed with hepatitis C in 2000.

Over the following decades, he received care from 2 different infectious disease doctors.

In 2016 the patient was started on 2 antivirals: a combination pill of ombitasvir, paritaprevir and ritonavir, as well as ribavirin.

The patient achieved sustained viral response and was considered effectively cured of hepatitis C.

Less than a year later, he developed abdominal pain and weight loss.

Workup revealed a large liver mass with pulmonary metastases.

He was diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Despite treatment, he died the following year at 55 years old.

Join thousands of doctors and attorneys on the email list.

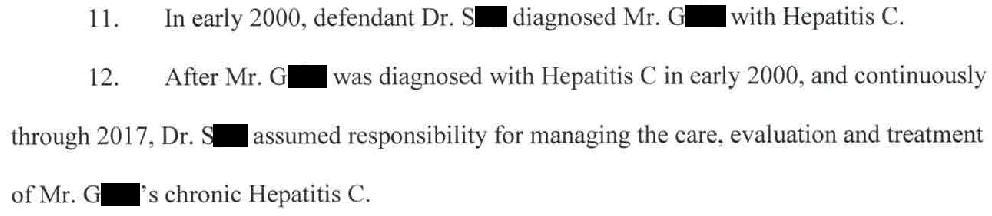

The plaintiff’s description of events and accusations are shown here:

His wife contacted a law firm and a lawsuit was filed.

The primary criticism was that the ID physicians did not perform recommended screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis, which consists of liver ultrasound (and debatably AFP testing) every 6 months.

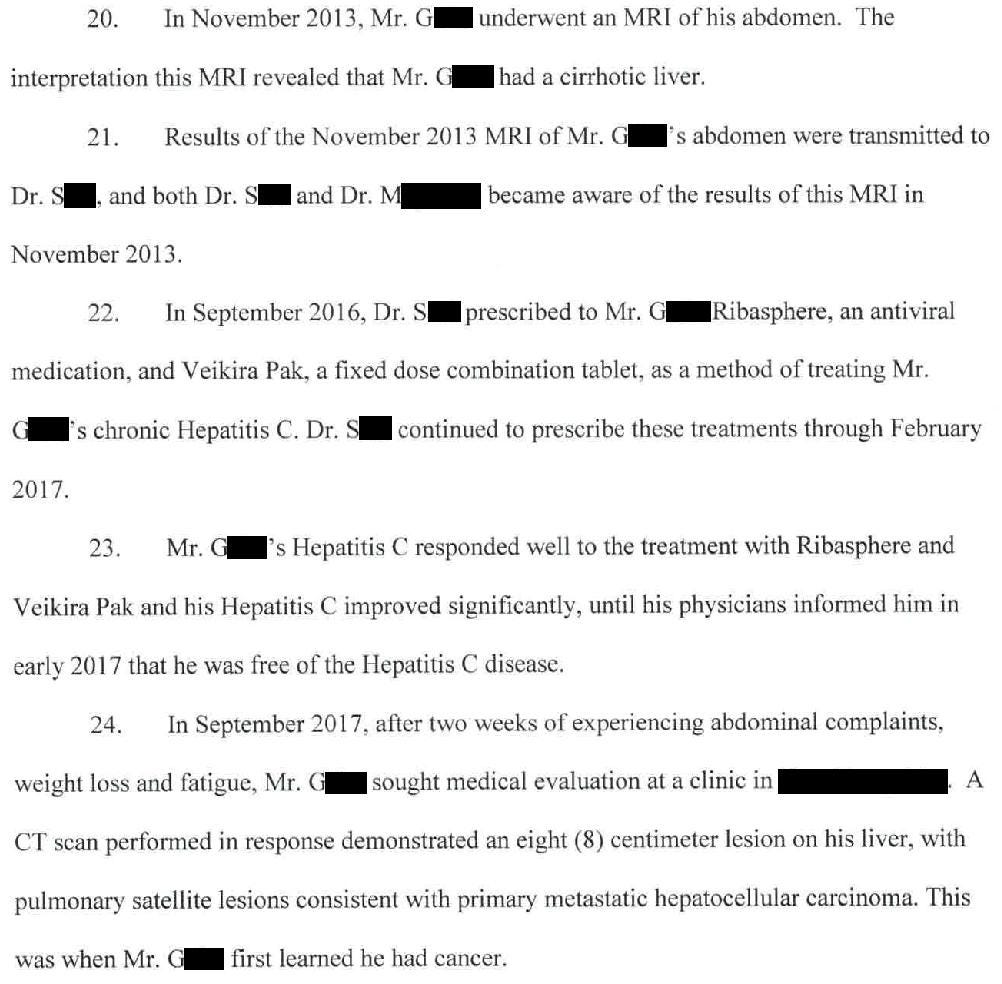

The expert witness opinion is shown here:

The defense hired their own ID expert.

Become a better doctor.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

The defense hired a physician epidemiologist who wrote that even if the screening guidelines were violated, there is no evidence that following these guidelines actually reduces hepatocellular carcinoma mortality risk.

The plaintiff hired a transplant surgeon who wrote that the patient likely would have qualified for a liver transplant if diagnosed earlier, which may have offered a chance of cure.

A confidential settlement was reached and the lawsuit was withdrawn.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

The key issue in this case is whether or not screening guidelines were in place while this patient was under the care of the ID physicians. It’s clear that current recommendations from the AASLD support q6mo screening for patients with cirrhosis (from any cause, not just hepatitis C), but these guidelines were published in 2023. The key time period in this case was 2013 (when his cirrhosis was diagnosed) through 2017 (when he was diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma). I had a surprisingly difficult time finding AASLD guidelines that would apply to this time period. There are multiple references to 2010 AASLD guidelines but either these guidelines did not address HCC screening or they are not preserved anywhere online that makes them easily findable. There are papers from this time period that address q6mo screening, but it’s not clear if this research had made it into formal society guidelines. I don’t think it’s reasonable to hold doctors responsible for ongoing research that has not yet made it into society guidelines. It can be difficult to determine when research results becomes the standard of care. Additionally, I find it troublesome that these experts do not cite any specific literature to support or defend this doctor.

The delineation in responsibility between infectious disease and gastroenterology is not clear. Who should be responsible for screening these patients? On one hand, every ID doctor knows about the risk of HCC in hepatitis B and C patients. On the other hand, it’s understandable that management of cirrhosis and cancer screening may not be their primary focus. GI is much better equipped to manage cirrhosis and they already frequently deal with cancer screenings (albeit related to screening colonoscopies). As with many topics in medicine there is significant overlap between specialties, which is why it is so important to maintain a curious attitude and remain widely read.

I’ve published multiple malpractice cases related to poor follow-up of incidentally-identified lesions, but I believe this is the first case I’ve covered related to failure-to-screen. Screening guidelines are becoming progressively more complex, especially as we identify more niche patient populations that can benefit from screening. I suspect we will begin to see more and more of these lawsuits as guidelines become progressively more complex. Further complicating matters, it does not appear that there is any single authoritative source of cancer-screening recommendations (let alone topics outside oncology) that aggregates these guidelines. USPSTF may be the closest, but is silent in regards to HCC screening in cirrhotic patients.

One of the more interesting points that the defense expert made was that even if screening guidelines were followed, these guidelines may not actually reduce mortality from HCC. I found this to be a particularly interesting criticism, because reducing morbidity and mortality is the entire point of these guidelines. If earlier diagnosis provides no improved outcomes (after accounting for lead time bias), then screening is worthless. Proving mortality benefit is key to widespread adoption of cancer screening approaches (colonoscopy for CRC, low-dose chest CT for smokers, etc…). One point of discussion is that screening may reduce disease-specific mortality, but not all-cause mortality. I do not consider myself an expert on cancer screening expert but I think it is wise to understand the basic points of debate around this topic.

One of my weird hobbies is reading about oncoviruses. I remember as a child seeing a rabbit with a weird growth on its face, and my father (who has a PhD in virology) taught me about Shope papilloma virus. Oncoviruses aren’t really directly applicable to my practice in EM but it’s a fascinating topic that has repercussions throughout all areas of medicine and public health. I’ve published 2 other oncovirus malpractice cases, both related to HPV. One related to head and neck cancer that killed a patient via carotid blow out syndrome, and a cervical cancer case. Hopefully I can find some EBV, Merkel cell polyomas virus, HTLV, or other weird oncovirus cases to share with you all!

In reference to Med Mal Reviewer's point #3...the dilemma that he refers to regarding keeping track of authoritative recommendations for screening is only going to get worse and our ability to recommend and order the appropriate screenings through a patient's insurance is only going to diminish as the present anti-science/anti-research/anti-ACA administration continues to dismantle many of the public health agencies, programs, and insurance requirements that we have depended on for these purposes.

E.g.--

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/save-uspstf-2025a1000cv8

"The USPSTF is not being dissolved, but its authority and the future of free preventive care access under the ACA are being challenged in the courts."

As a pediatrician, it is my fear that our current anti-vax Secretary of HHS will find a way to overturn the requirement of insurance companies to cover preventive care visits, screenings, and childhood vaccinations with no out-of-pocket cost to patients and their children.

Although Infectious disease doctors are internist by training, i find it troubling to have them shoulder the burden and responsiblity of anything outside of their specialty training and focus. There is simply too much information out there for anyone one doctor to know and know well outside of their training. It would be a ridiculous and unjust standard to hold doctor's responsible for the medical knowledge outside of their specialty. I can imagine internist being called for not knowing surgical standards. This is just another example of a malpractice lawyer seeing dollar signs from a tragedy and contributing to the fall and ruin of medicine.