An otherwise healthy 9-month-old boy was seen by his pediatrician (Dr. E).

Overall he seemed to be doing well, but his mother reported that he sometimes collided with objects in front of him.

A normal eye exam was documented, although notably without mention of red reflex.

At the next visit, he underwent a spot vision screening that suggested anisometropia.

The child was given a referral to see an ophthalmologist.

At the ophthalmology appointment, Dr. K examined the child’s eyes and noted blepharitis and intermittent esotropia.

The child’s mother later claimed that she wanted to discuss “yellowness” of his right eye, but that Dr. K seemed dismissive and there was a language barrier.

Over the next few months his mother continued to notice that he was bumping into things and falling.

She saw a Facebook post with a picture of a normal red reflex and an abnormal light reflex, which recommended seeing a pediatrician to be evaluated for cancer. She felt her child’s eyes had the exact same appearance as what she had seen on social media.

This was discussed at the next visit but the pediatrician was not worried about his eyes because he had already been seen by the ophthalmologist without any significant concerns.

Become a better doctor.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

His mother asked to see the ophthalmologist again.

Dr K again did not find any significant abnormality but did recommend he come back for a dilated exam in a month.

His mother was unsatisfied with this, so she asked the pediatrician for a referral to a different ophthalmology office.

At the new office, an optometrist thought he might have cataracts.

The child’s mother was told to return in a week to see the pediatric ophthalmologist.

At the return visit, he was diagnosed with a large retinoblastoma in the right eye with retinal detachment, and smaller areas of retinoblastoma with detachment in the left eye.

After exam under anesthesia, he was definitively diagnosed and underwent a prolonged treatment course.

Unfortunately, the child lost vision in both eyes.

A lawsuit was filed against the pediatrician and ophthalmologist.

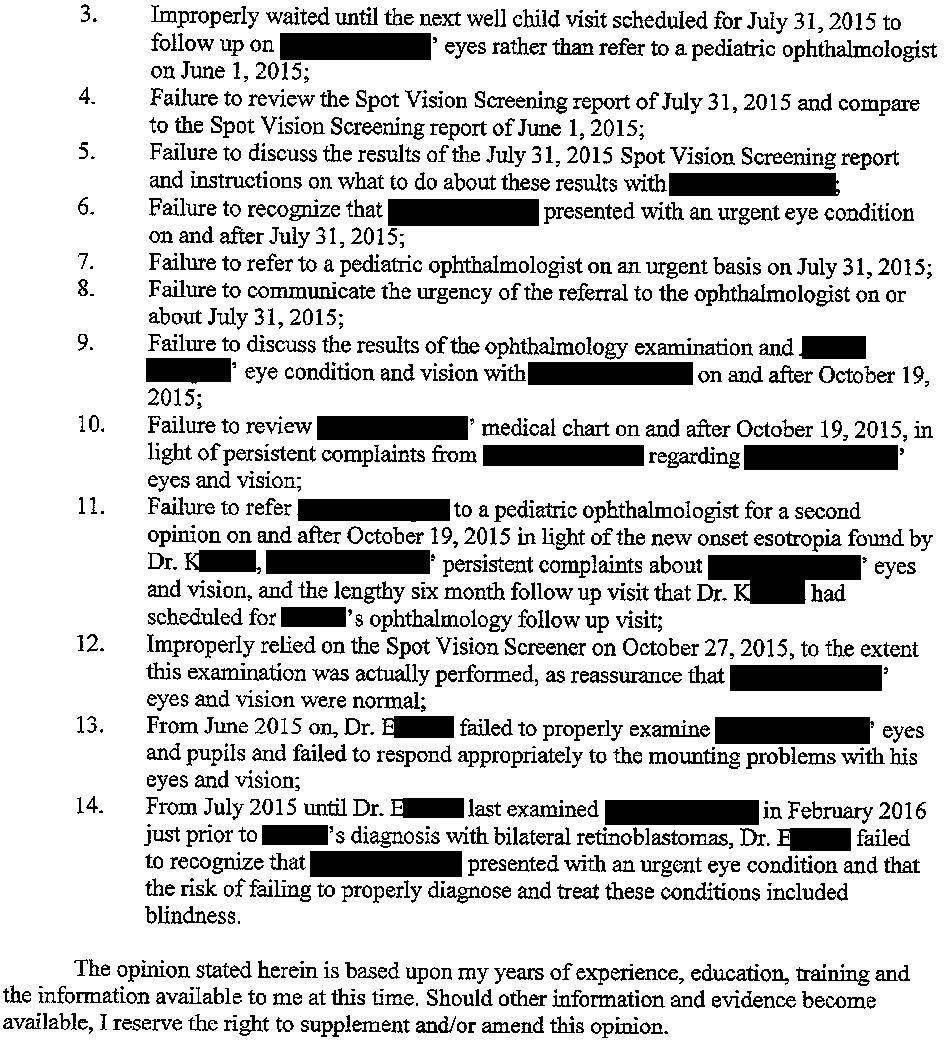

The plaintiff’s pediatric expert opinion is shown here:

The ophthalmology expert report was copied verbatim in regards to the first 23 numbered paragraphs.

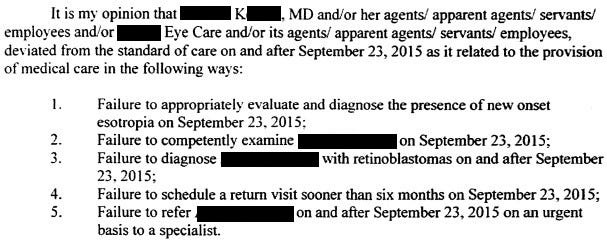

The specific deviations from the standard of care are listed here:

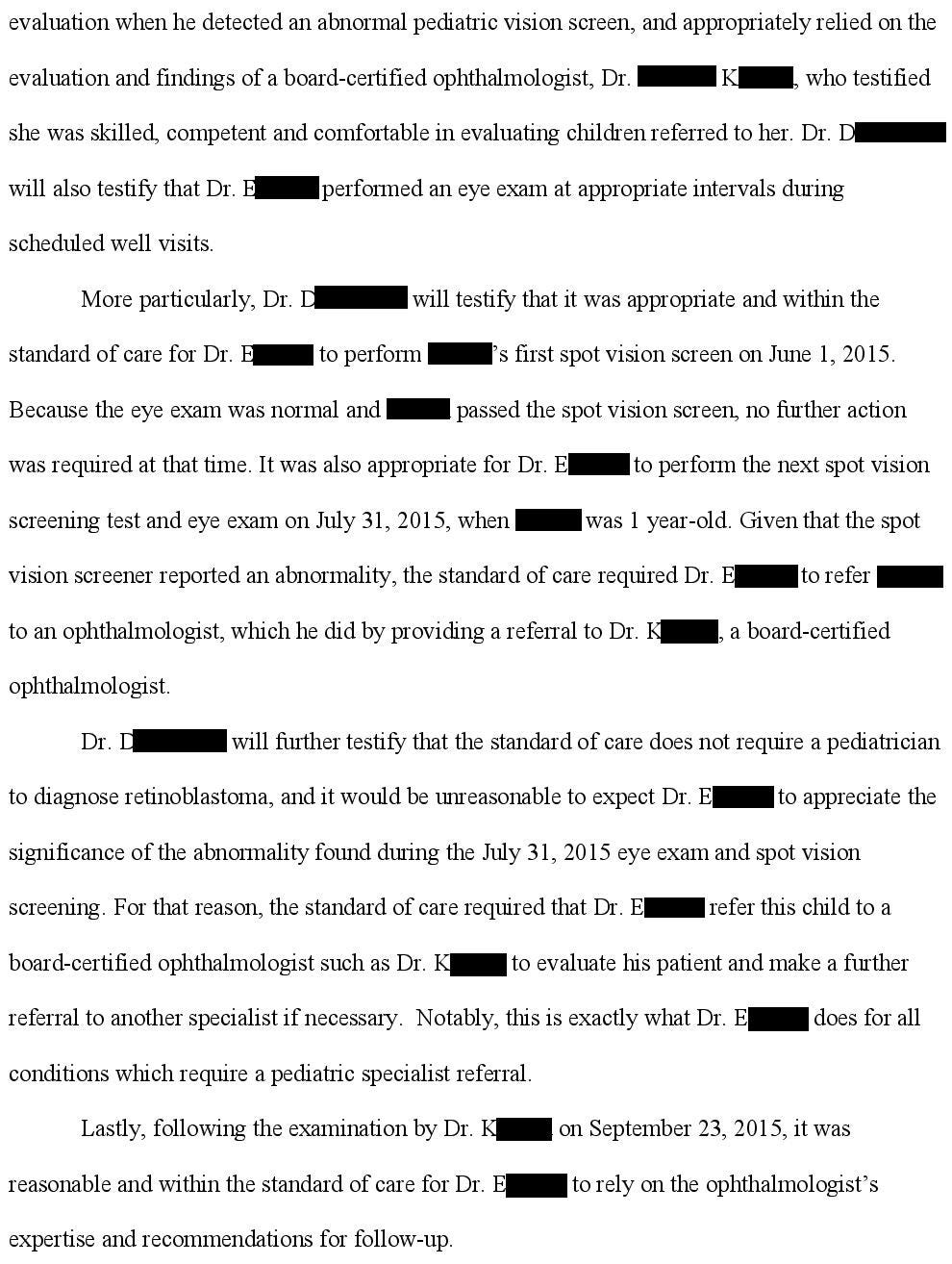

The defense hired a pediatrician to defend Dr. E.

The defense hired an ophthalmologist to defend Dr. K.

They argue that despite missing the diagnosis, earlier treatment would not have changed the ultimate outcome.

The lawsuit is ongoing.

Subscribe to receive updates as they occur.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

It seems like the language barrier in this case played a significant role in the delayed diagnosis. The patient’s mother speaks Spanish. The lawsuit didn’t specifically mention a failure to use an interpreter but I am suspicious that they tried to get by using a combination of broken English and broken Spanish. Not only does this significantly limit the history and exam, it also limits the logistics of accessing healthcare including calling to make appointments.

It’s pretty embarrassing that the mother correctly diagnosed her son’s disease by looking at a Facebook post, and yet it was missed by several physicians. We all know the trope of the worried mother consulting Dr. Google and ending up at some very bizarre conclusions, but in this case it was just the opposite. “Don’t confuse your Google search with my medical degree” turned into “Don’t confuse your medical degree with my mommy blog diagnosis”. Stay humble or this will happen to you too.

The pediatrician’s documented eye exam was exactly the same on the July 31, October 19, and October 27 visits. It’s clear that he was simply copy/pasting the same exam onto all his charts, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing as long as it’s accurate. Every single doctor reading this newsletter uses templated exams to expedite documentation, including me. The problem is that when the patient’s mother is repeatedly and specifically mentioning a “yellow” eye, you have to move beyond the templated exam and actually write something specific to the patient. It’s worrisome that an outpatient pediatrician’s eye template didn’t include any mention of the red reflex. Including this exam finding in his template may have helped him remember to address one of the primary medicolegal ocular risks facing outpatient pediatricians. If used correctly, templated exams can help you remember the correct exam in real time, and also provide defensible documentation when reviewed retrospectively.

Want CME credit for reading these cases?

Course evaluation to claim your CME credit for all March cases goes out later today.

Upgrade to a CME plan to claim your credit.

This case is absolutely heartbreaking. I'm bilingual (medical school in Mexico, residency in the US) and there have been a few occasions that I have relied on interpreters to ensure that Spanish speaking patients are clear on diagnosis, treatment plan, return instructions. Cultural factors that are not present in English speaking culture can also play an important role.

There seems to have been so much bias in this patient's care-minimizing mother's concerns, ignoring red flags, dismissing a major diagnosis. Racial, cultural and gender bias can affect patient care to such a degree, and no progress is being made to improve it. in fact, seems to be going backward.

This is awful. The ophthalmologist defense is shameless. The difference between total blindness, loosing one vs two eyes, vs seeing shapes and colors are all very different outcomes. They absolutely dismissed this parent and child. A kid falling so much should have been taken more seriously, if not retinoblastoma, there are other CNS abnormalities and tumors to consider.

The fact the pediatrician kept billing for some eye procedure is absurd, he didn't do anything useful and is just as guilty as the ophthalmologist. He only checked a white reflex after the diagnosis, ridiculous.