A 72-year-old woman presented to the ED with epigastric pain and elevated temperature in August 2015.

A large pancreatic pseudocyst was discovered on CT.

GI was consulted and she was seen by Dr. V.

She underwent an endoscopic pseudocyst drainage via a cystogastrostomy catheter that was left in place. It was done by a second GI physician, Dr. W.

Following the procedure she also developed gram negative sepsis.

After hospitalization she was discharged on ciprofloxacin for 7 days.

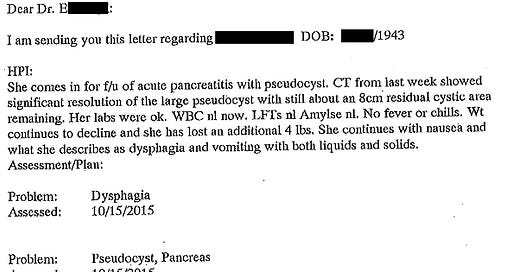

She followed-up with Dr. V in his office twice during October.

The patient continued to have weight loss, nausea, and vomiting.

Dr. V wrote a note to her primary care doctor.

An EGD was done on October 19 without any explanation for the patient’s ongoing dysphagia.

Dr. W did the ERCP on November 12.

An additional pancreaticogastrostomy catheter was placed to allow the rest of the pseudocyst to drain.

A stent was also placed in the pancreatic duct.

Following the procedure she had persistent hypotension and bradycardia that required fluids and pressors.

She was admitted for a week and discharged on antibiotics again.

On November 30, she presented to the ED with hypotension, fatigue, and vomiting.

She was seen by 2 EM attending, Dr. W and Dr. H.

Fluids and antibiotics were ordered.

Her blood pressure improved and she was admitted to the step down unit.

Over the next day it became clear she was septic.

Ongoing fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, and pressors were ineffective.

She died on day #3 of hospitalization.

The patient’s family filed a lawsuit against the EM doctors, both gastroenterologists, and the hospital.

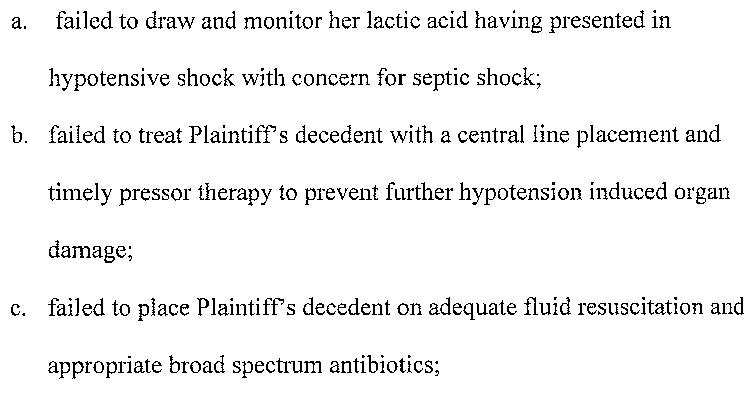

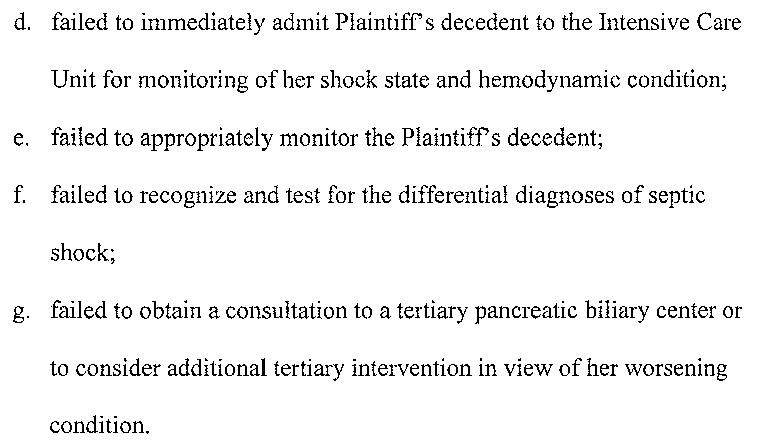

The allegations against the EM physicians are shown here:

Be a better doctor by reviewing malpractice cases.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week.

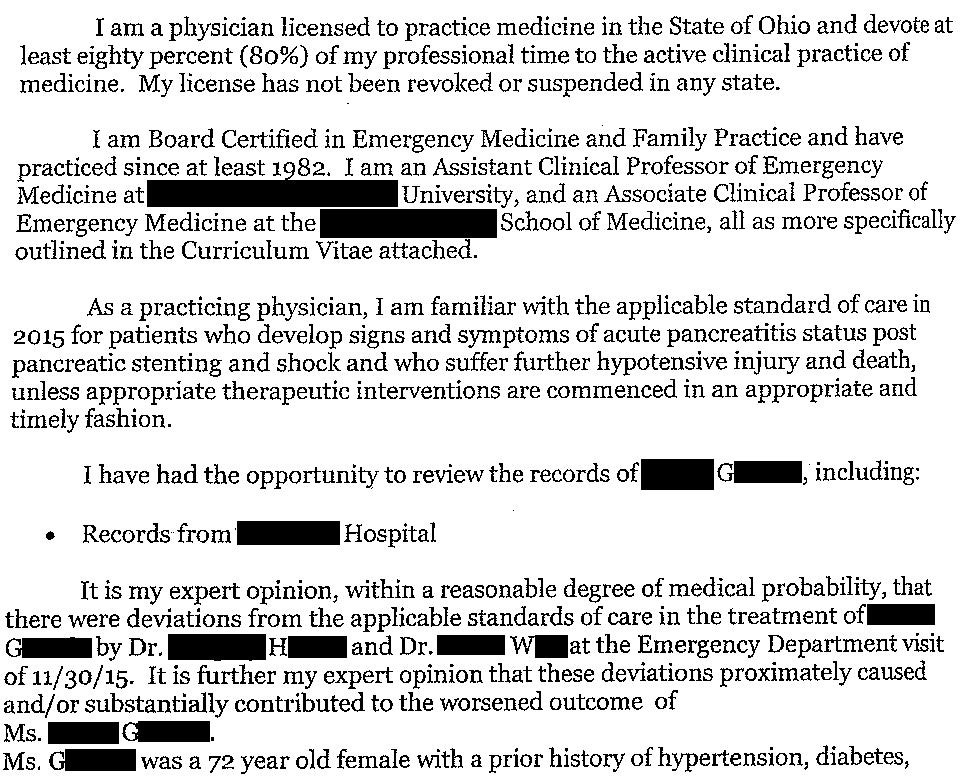

The plaintiff’s EM expert opinion is shown here:

The plaintiff’s GI expert opinion is shown here:

Improve your understanding of medicolegal topics.

Learn about common pitfalls that aren’t taught in medical education.

CME subscription is available for those who want to claim credit.

The defense hired their own EM expert, who also did a neurocritical care fellowship.

The plaintiff has offered to settle for $350,000 from each of the physicians.

The lawsuit is ongoing.

I’ll update readers as new developments happen.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

The accusations against the EM physicians need more detail if they are to be taken seriously. I probably would have checked a lactate in a recently septic bounceback with hypotension, but the causation argument (failing to check a lactate caused the bad outcome) is extremely flimsy. The standard 30cc/kg fluid bolus in the ED is not affected by the lactate (although it may help guide downstream resuscitation). They were criticized for not giving enough fluids, but it’s not clear how much they actually ordered. Persistent hypotension after fluid resuscitation can be an indication to start pressors (which may or may not require a central line), but the reported BP of 89/56 is barely hypotensive (per the systolic blood pressure) and translates to a MAP of 67. If other clinical signs of shock were present (altered mentation, mottled skin, etc…) there could be an argument for it, but it’s a gray area that requires case-by-case assessment, not sweeping generalizations. Admitting the patient to step-down vs ICU is up to the admitting doctor, not the EM doctor. And since the patient was getting all of her care at this hospital, there was no reason to send her to a “Pancreatic Center for Excellence” (whatever that is). These criticisms may have some validity but the experts absolutely failed to support their arguments with facts.

Antibiotics were started, although I really wish either side would specifically mention which antibiotics were given so we could make an assessment. The plaintiff seems to suggest that they didn’t provide broad coverage, and emphasizes the possibility of anaerobic organisms. One educated guess is that the ED gave ciprofloxacin, which they may have felt was reasonable given she had been successfully treated with it previously. Cipro monotherapy is neither broad spectrum nor would cover anaerobes, explaining the plaintiff’s criticisms. This case illustrates why basically all ED sepsis care is now dictated by order set, as mandated by hospital policy and government requirements. 30mL/kg crystalloid and broad spectrum antibiotics (almost always vanc/Zosyn) are forced on nearly every patient. Sometimes this approach is unnecessary and can even cause patient harm, but in cases like this there is an argument that it may improve patient outcomes.

The accusations against the GI physician seem to focus on the length of antibiotic therapy and the decision to do another ERCP for stent exchange. The plaintiff’s GI expert offered the theory that complications from the ERCP caused her to become septic again, but it seems odd that it would take 18 days for hypotension to develop if this was truly the primary exacerbating factor. It’s not completely ridiculous but I don’t think anyone could state this with any degree of medical certainty.

I often see lawsuits alleging that a procedure was performed negligently, but I don’t see many lawsuits like this one in which the plaintiff alleges a procedure shouldn’t have been done in the first place. It’s interesting that one of the previous lawsuits I’ve published alleging that a procedure should not have done was also about an ERCP. The patient in that case had a hypoxic arrest, and the GI doctor settled before trial.

I have so many thoughts, but these are my initial ones:

1)This case touches on one of my pet peeves as an intensivist: serum lactate is one of the most overrated and overutilized lab tests in medicine.

Yes, an elevated lactate can help you identify a patient that's sick, and that you need to pay closer attention to (you can argue the history, vital signs, and exam should accomplish that anyway). But it has very little utility in guiding therapy. In fact, following it serially can be actively harmful at times, because it can lead to a waterlogged patient from clinicians trying to make it go away with endless fluid boluses.

It can even be troublesome for prognostic purposes. I've seen so many cases where the lactate goes up., down, and sideways, yet the patient is off pressors, extubated, and sitting up in a chair having a conversation with me. Conversely, I've seen plenty of cases where the lactate clears by day 2, and the patient is still in trouble.

Don't get me wrong, the lactate can be useful in specific circumstances, but it needs to be interpreted in context, and it's limitations understood. I'm extremely skeptical getting a lactate level would have made any difference at all in this patient's outcome.

2)One of the criticisms is inadequate fluid resuscitation. Pancreatitis, along with pre-ecclampsia is one of the most frustrating diseases when it comes to fluid management. Too little, and you have inadequate circulating blood volume. Too much, and the capillary leak causes all kinds of third spacing, organ edema, and respiratory failure. It always feels like whatever you do, it's the wrong answer.

3)I question how much of a difference ICU vs ICU Stepdown admission would have made. In my shop, at least, ICU Stepdown is run by the critical care team, and just across the hall from ICU. If someone seems to be doing okay initially, but then becomes hypotensive, it doesn't involve much in the way of time delay to start pressors and move them over. The "early central line" dogma is a residual of the Rivers trial, has been debunked, and is not really standard of care anymore: We will place a line if we can't get adequate or safe peripheral access, if the pressors doses keep escalating, or if the patient is on pressors for more than 24 hours (this is more hospital policy rather than based on evidence).

I didn't see any details about whether the patient had a prolonged period of hypotension before it was recognized and pressors were started, whether one of her PIVs running a vasopressor infiltrated, or whether the ICU team dragged their feet in placing a central line. Again, none of this has anything to do with the ED doc.

Damned if you do, damned if you don't. I'd argue the stent had to be exchanged since patient has persistent nausea/vomiting and losing weight, clearly not thriving. If she had died of malnourishment, dehydration, renal failure, they would be suing for not doing the stent exchanged/ERCP.

The ED doc being added on to lawsuit seems absurd. Pt probably got assessed, admitted , and received abx/IVF, which is in a stable fluid-responsive patient is appropriate care. ICU vs other bed admission is not up to EM doctors! Unless they gave minimal to no fluids or did nothing with patient being persistently hypotensive, then Idk why they got dragged into this.