A 49-year-old police officer was sitting in his patrol car at 3:45pm when he purposefully twisted his neck to the side to crack it, but felt an unusual pop.

He immediately developed dizziness, nausea, and double vision.

Another officer noticed he did not look well, and called for an ambulance.

The patient was triaged in the ED at 4:57pm and seen by Dr. M several minutes later.

A CTA head and neck were ordered immediately, and completed at 5:51pm.

At 7pm, Dr. M’s shift ended and Dr. H took over.

Dr. F (radiologist) called with a critical result at 7:20pm.

While waiting for the CT results, the patient’s family and colleagues had noticed his condition worsening.

Dr. H went to see the patient after receiving the phone call, and noted right arm and leg numbness, as well as trouble swallowing.

She called a nearby academic center for a neurology consult.

At 8:01pm, she spoke with Dr. W, a stroke neurologist.

He requested the images be sent and that he would call her back.

At 8:47pm, Dr. W called back.

He advised against giving tPA and to start Plavix.

The patient was accepted for ED-to-ED transfer.

The patient worsened en route.

An EM resident at the receiving hospital wrote the following note:

His condition continued to decline.

Neurosurgery took him for a posterior decompression and EVD placement.

The patient suffered a PEA arrest but had ROSC after several rounds of CPR.

He initially was diagnosed with locked-in syndrome but began to improve.

The patient received a trach and G-tube.

He could communicate with letter scanning and a Dynavox tablet.

After several months he was weaned from the ventilator.

Sadly, the patient died of COVID at a rehab facility during the pandemic.

Become a better doctor by reviewing rare and challenging malpractice cases.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

The patient’s family filed a lawsuit against multiple physicians, the ambulance company, and both hospitals.

Numerous physician expert witnesses were hired by both sides.

This state does not require disclosure of written expert witness opinions.

Instead, deposition excerpts from the plaintiff’s neurology expert are shown here.

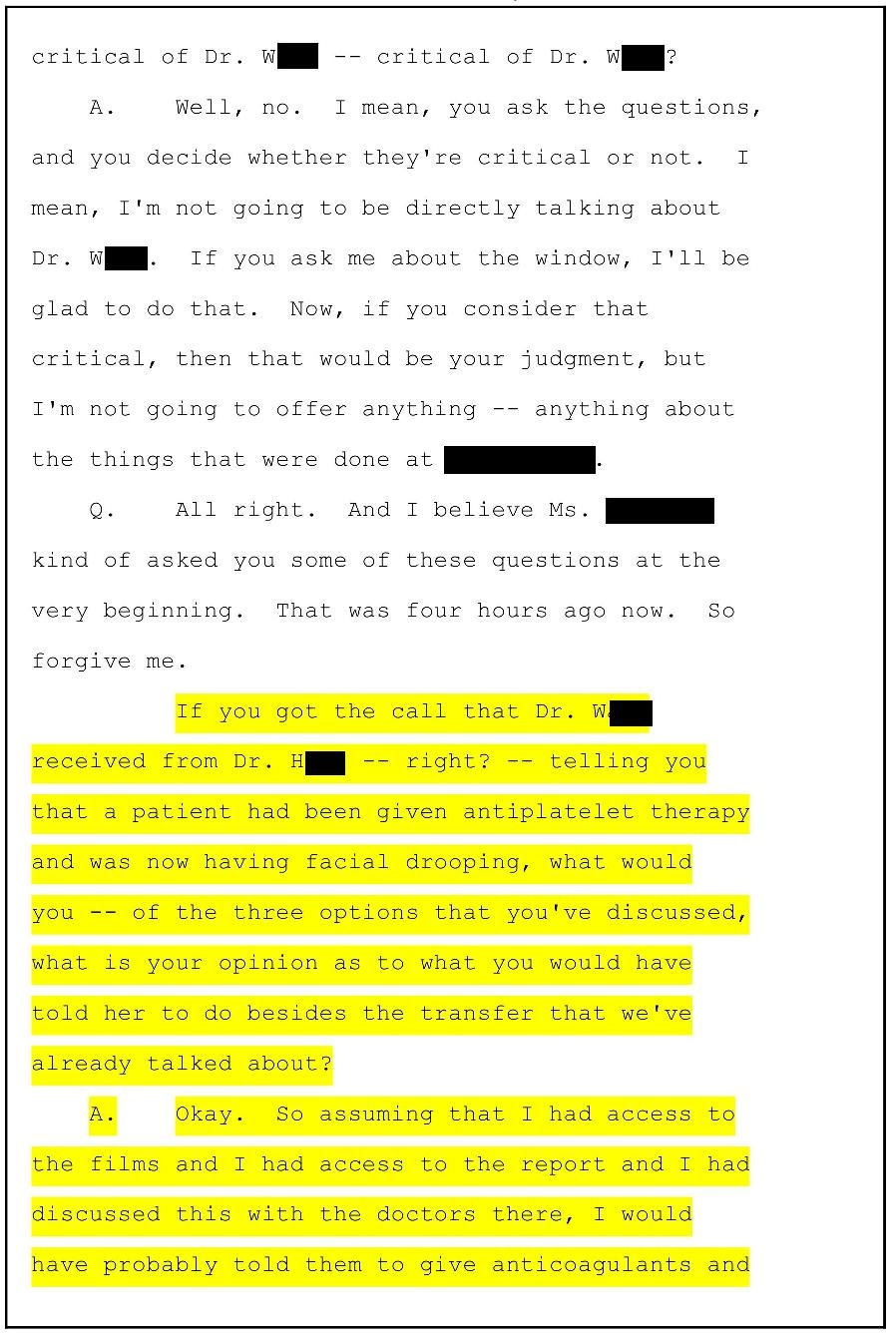

In this section, the defense attorney is asking about the neurologist’s claim that heparin should have been started before transfer:

In this excerpt, the defense attorney is asking about the neurologist’s claim that tPA should have been given:

Finally, the defense expert asked the plaintiff’s neurologist if he was doing to offer any criticism of Dr. W, the neurologist who took the phone call after the dissection was identified.

The ambulance company settled with the plaintiff for $943,745.54.

Join thousands of doctors and attorneys on the email list.

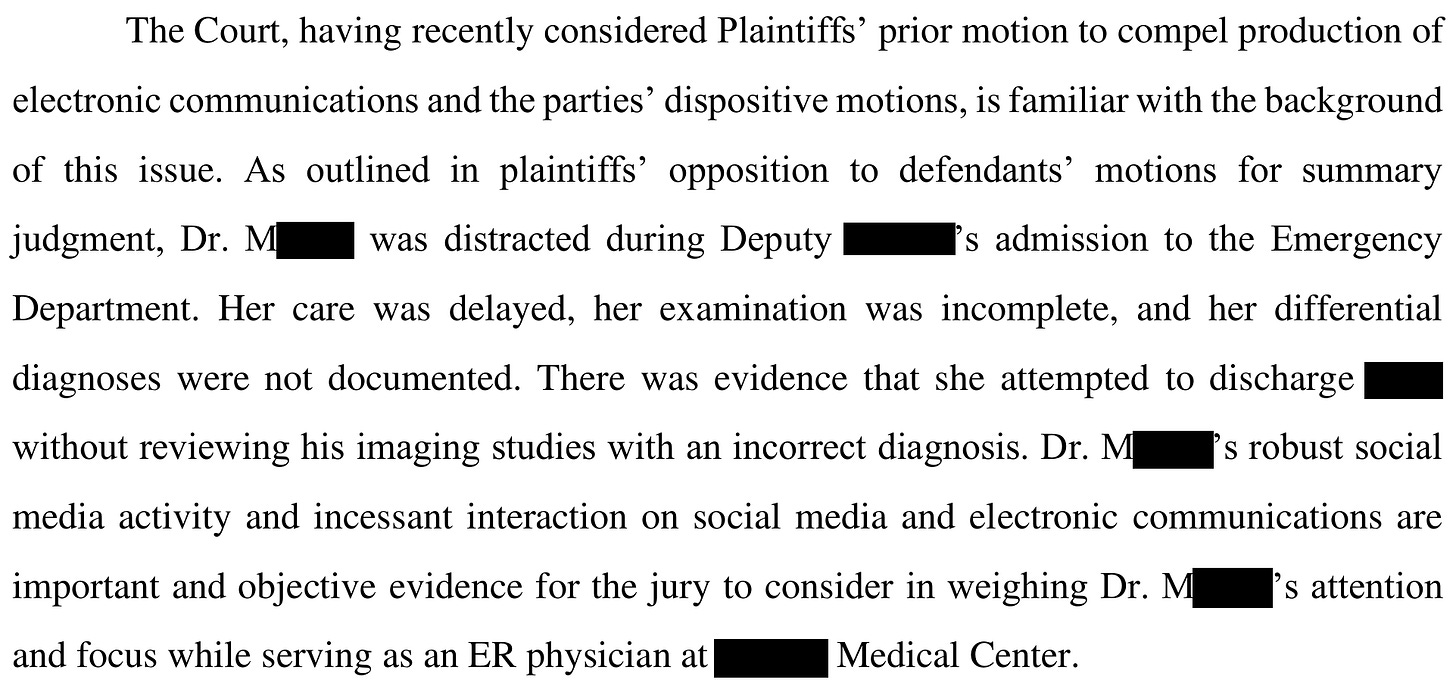

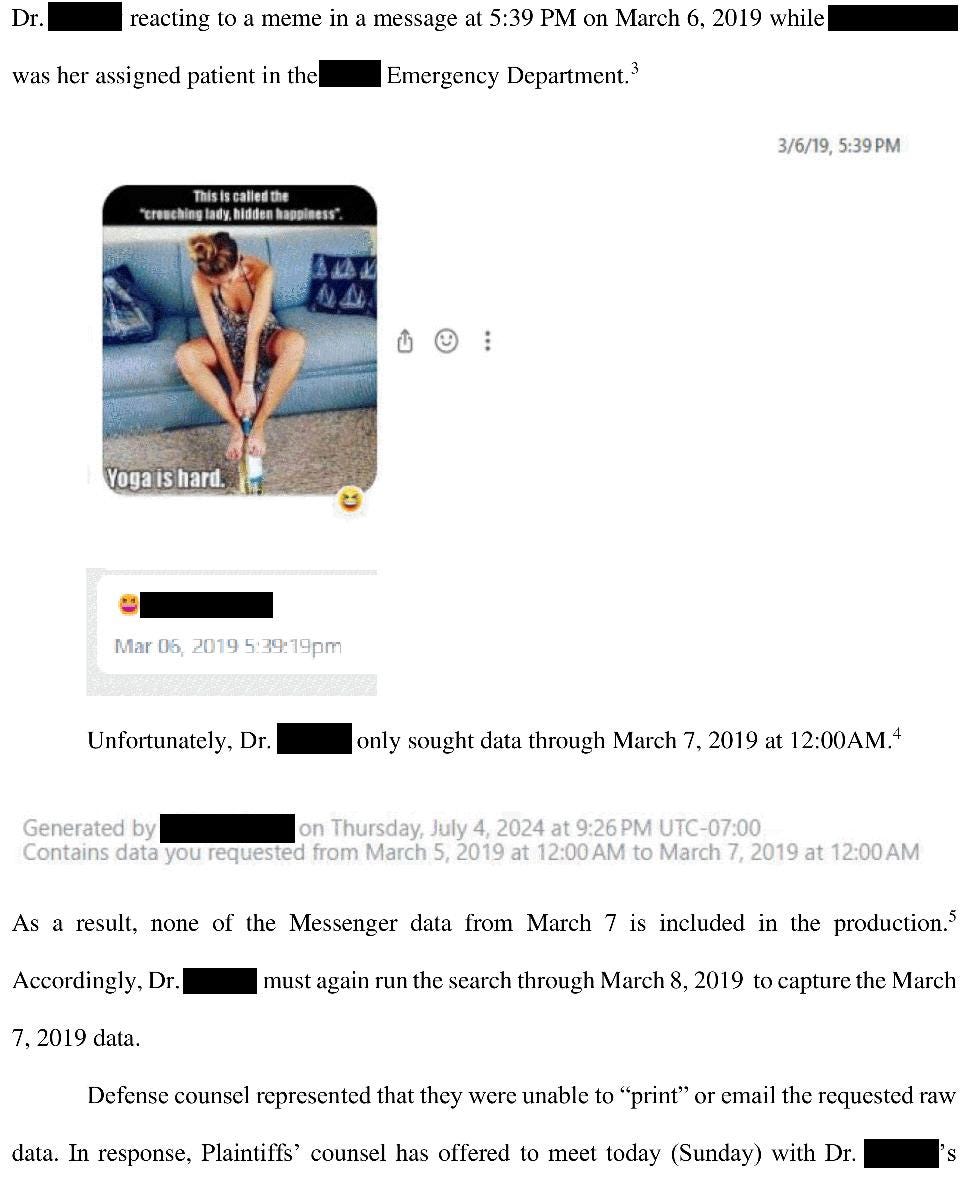

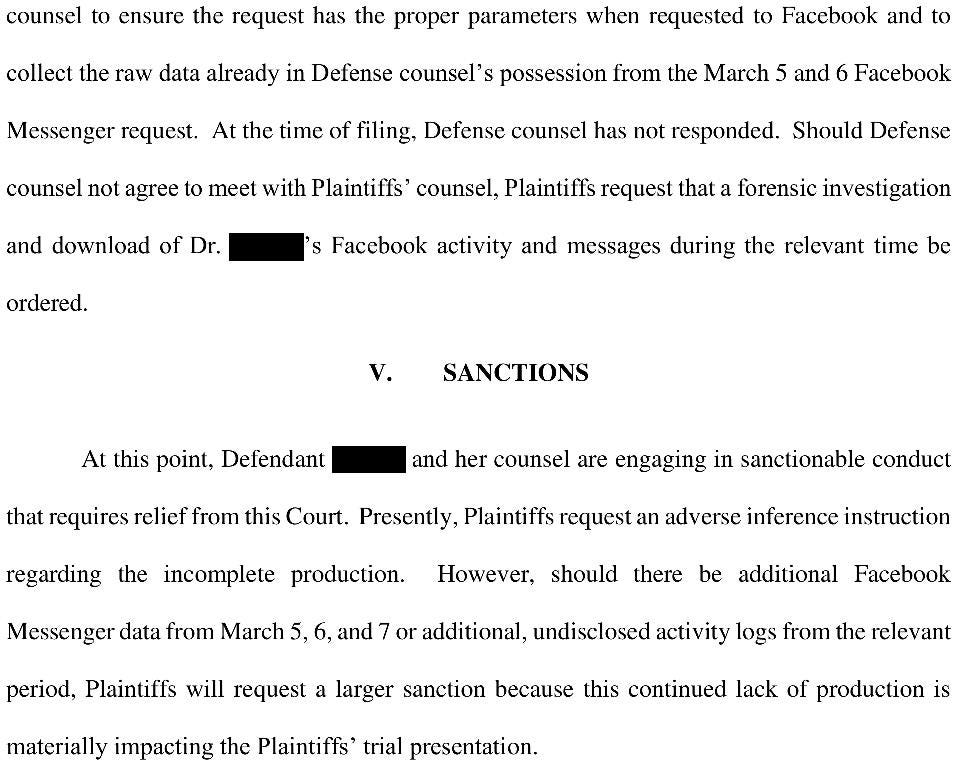

The plaintiffs somehow became aware that one of the ED physicians had accessed Facebook on their phone while the patient was in the ED.

The judge ordered the physician to give the plaintiff a log of all Facebook activity during a multi-day time period.

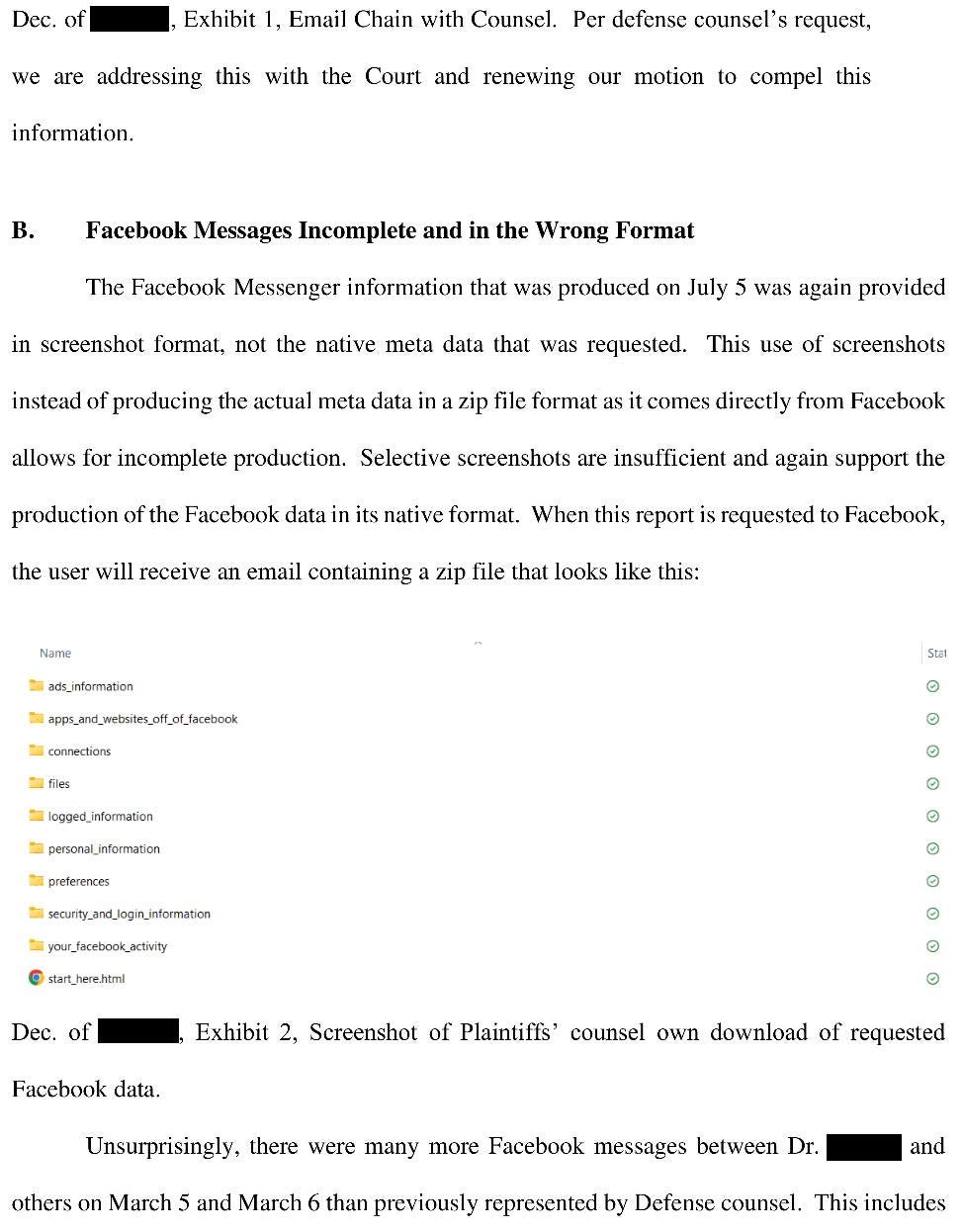

The plaintiffs allege that the physician willfully disobeyed the judge’s order, only turning over a few screenshots as opposed to the entire raw data of all of their Facebook activity.

The trial started on July 1, 2024.

It is still ongoing.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

Part of me understands why this patient didn’t get a stroke activation. Most patients with peripheral vertigo in the ED have nystagmus and can’t walk due to the dizziness. It’s not practical or appropriate to call a stroke activation on every dizzy patient. However, the history of neck self-manipulation coupled with ataxia and nystagmus demanded a more aggressive response. Its not clear if that history was provided to the physician.

The doctor’s Facebook usage is an interesting twist. I’ve seen a doctor’s personal phone records get used at trial before (when used to communicate with a consultant), but I’ve never seen the plaintiff’s attorney go so aggressively after multiple days of social media records. The fact that the defense is not complying with court orders to turn over these records is worrisome and could lead to even worse legal repercussions. The plaintiff is clearly suspicious that she was active on Facebook throughout the entire case, not just a brief break (but its unclear thus far if this is true or not). Personally I think its fine to look at your phone if you’re taking a mental break and are just waiting for results. However, its easy for a plaintiff’s attorney to make you look incredibly bad for being “distracted” by social media, and I bet the jury will not view this kindly. Its not clear how they even knew to request this information. It will be interesting to see if plaintiff attorneys start routinely requesting social media data in more malpractice cases, just to see if they stumble across something they can use to insinuate that the defendant was distracted.

The plaintiff’s expert witness made several claims that I find to be inappropriate. He initially claims that heparin isn’t 100% effective, but then later says its “always effective” in his experience. He is advocating that there should be no time limit for giving thrombolytic, which is simply not supported by guidelines nor the standard of care. I’m not interested in using this newsletter to re-litigate the debate about tPA, but suffice it to say I think this expert gave poor testimony that will mislead the jury.

This case has some very significant parallels with the last vertebral artery dissection / basilar clot / posterior circulation stroke case I published. Its worth comparing them side-by-side to tease out some similarities:

Both were caused by neck manipulation.

The onset of symptoms was instantaneous.

Both EM physicians immediately recognized the concern for dissection and ordered a CTA head/neck, yet there was still a catastrophic outcome and the doctors got sued.

The radiology reports in both of these lawsuits use the word “dissection” but in a verbose manner that could be somewhat perplexing to a clinician. I don’t necessarily blame the radiologists for this, because there may be some uncertainty inherent in the images. However, for those of us at the bedside, you should know that the report for a dissection may be somewhat circuitous and may require reading between the lines. If the radiology report describes any sort of “filling defect” or “stenosis” or “the right vertebral artery does not contribute to the formation of the basilar artery” or anything indicating the contrast is not making it through the artery in a normal fashion, there’s a chance it’s a dissection.

Another common theme in stroke malpractice cases is the alleged failure to activate a Code Stroke. Every step gets expedited during a stroke activation: time to CT, time to getting the radiology report, and time to getting a neurology consult. In addition to these two posterior circulation stroke cases, I also published a case in which a patient arrived with a chief complaint of “unresponsive”, there was no stroke activation, and there was a delay in diagnosis. We’re pretty good at calling stroke activations when patients clearly state they are having unilateral weakness, but we’re not as good with other stroke presentations.

Some will argue that HINTS should be used in this situation. I personally do not find it useful and retain deep skepticism of its clinical utility in the ED. The head impulse testing is particularly impractical. Patients do not keep their eyes open, there is a high risk of them vomiting on your arms while you hold both sides of their head, the findings are extremely subtle, and it seems wrong to jerk a patient’s head side-to-side in a manner that is strongly reminiscent of the mechanism that caused the dissection in the first place. I particularly enjoyed this article about HINTS and a more applicable approach the authors dubbed “dizziNIHSS”.

One reason that vertebral artery dissections are so medicolegally dangerous is that patients can initially present with very minor symptoms, but may not progress to a debilitating stroke until they are outside the intervention window. This is further complicated by the fact that there is often significant clinical overlap in the presentation between benign vertigo and posterior circulation stroke. Furthermore, these posterior circulations strokes are particularly catastrophic. A locked-in patient will require massive lifetime support, and their severe disability really tugs at the heart strings of a jury. This is one of my most feared clinical scenarios and diagnoses.

One good learning pearl for students and residents is to simply recognize the awful trifecta of vertebral artery dissection, basilar artery thromboembolism, and catastrophic posterior circulation stroke. They go together like the 3 musketeers of severe disability. Each entity can lead to the next. A vertebral artery dissection should not be considered in isolation, always keep in mind the potential downstream consequences.

As a neurologist it’s important for me to note that intracranial vertebral dissections are associated with high risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage (up to 50% in some literature) so the discussion of heparin drip is not as straightforward as the plaintiffs “expert” seems to suggest.

That expert's testimony is absolutely bonkers and it feels like the defense attorney went pretty soft on him. He explicitly says he doesn't follow guidelines (which is pretty obvious given that he's saying the standard of care for a vert dissection is tPA). Even the evidence for heparin as opposed to antiplatelets doesn't really exist and anticoagulation is explicitly not recommended for intracranial dissection. Doing anything short of straight up calling him a clown seems like a missed opportunity.

It's beating a dead horse, but the fact that someone can be presented as an expert and not only not back up their assertions but explicitly state they aren't based on guidelines or scientific studies is an absolutely damning indictment of our legal system and a huge argument against lay juries for these kinds of cases.